Australasian Journal of Irish Studies, Vol. 13, 2013

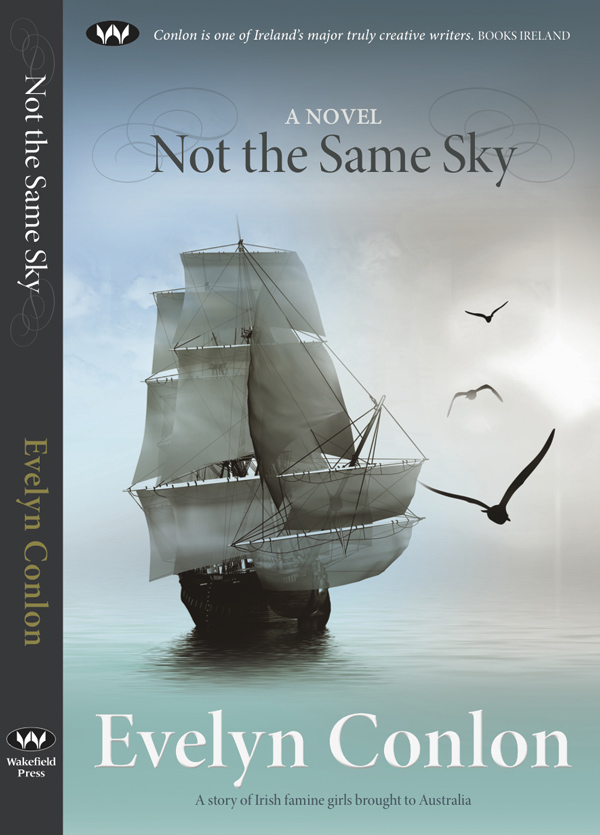

Review of Evelyn Conlon, Not the Same Sky. Wakefield Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1-74305-242-6. PB. 251pp. $24.95.

Evelyn Conlon’s latest novel, Not the Same Sky, is based on the true story of the, roughly, 4000 Irish Famine orphan girls who were shipped from Ireland to Australia between 1848 and 1850, a project that helped with two socio-political problems at once: the shortage of food in Ireland and the shortage of female labour in Australia. The narrative centres on one ‘shipment’ of girls, on the Thomas Arbuthnot in 1849, under the tutelage of Surgeon Superintendent Charles Strutt, whose selected diary entries relating to the journey were published in 1996. Readers familiar with Irish Studies in Australia will know this story well through such foundational texts as Trevor McClaughlin’s Barefoot and Pregnant? Irish Famine Orphans in Australia (1991; 2001) and Richard Reid and Cheryl Mongan’s A Decent Set of Girls (1996), both of which are acknowledged by Conlon as research sources for the novel. But whilst Conlon pays very close attention to the historical facts and figures of the background story, this is a long way from being a straightforward piece of historical fiction. The novel is not, in fact, about Ireland or Australia or the Famine or the girls themselves, for that matter – but, rather, uses all of these creatively to investigate the very notion of ‘memory’ itself.

The novel begins and ends in Dublin in 2008 with the life of a monumental stonemason, Joy Kennedy, who, by the very nature of her work, deals with the memorialising of names every day. On the basis that it might be appropriate to have an Irish stonemason involved in a planned memorial for the Irish orphan girls in New South Wales, Kennedy’s name is selected from a list for no other apparent reason than that she shares a surname with a member of the Memorial Committee. The use of the Prologue and final chapter to ‘book-end’ the body of the novel, provide a further structural emphasis on the novel’s themes of memory, memorialising and naming. But these are also closely linked in the novel to the concept of the journey – actual, physical journeys and those that take place inside the mind, as well as the relationship between them. At the beginning of the novel, Charles Strutt is a fastidious, kindly and competent administrator wholly concerned with the task of physically getting these girls safely from one side of the world to the other – a man who “didn’t think of himself as born for bravery or even excitement” (26). Yet, by the end of the novel, he is a man who has taken his own, unexpected journey and who has learned as much from the women as they have from him. The novel’s 35 short, vignette-like chapters, creates a diary-like effect, which is perfectly in keeping with the overall journey theme.

There are four central (fictionalised) Irish orphan girls at the centre of Not the Same Sky: Honora Raftery, Anne Sherry, Julia Cuffe and Bridget Joyce, though others are mentioned throughout, but Conlon has avoided the more usual thing of putting flesh on the skeleton of fact when dealing with the lives of these women. In fact, we don’t really get to know any of them very well at all. Births, deaths, marriages, remarriages, and a variety of other events in their lives all come and go and are noted – often in passing – but without any real sense of emotional engagement on our part. It would be quite wrong to assume, however, that this is a failure on Conlon’s part – she’s much too skilled a writer for that. Rather, the women are ‘types’ or representatives, if you like, of all the women who found themselves on the other side of the world, in a strange landscape and who knew, with absolute certainty, that they would never make the return journey. These women, in various ways, became defined by a line that split their lives into that which existed before the journey and that which existed after:

Ellen McGillicuddy … patted the heads of her children as they went out to school. She always had to remind herself to do it to all of them, not just the first. When she had looked at him on the second day of his life, she had said, ‘Well that’s that then. I’m from here now.’

Anne Sherry in Sydney started another hat.

Charles Strutt started another journey by sea.

Honora Taffe opened her trunk to clean it and took her bonnet out to air. She thought of herself as Raftery when she did this.

Julia Cuffe got on another coach.

It was Honora Raftery who realised what date it was. This time she wrote it down so she would remember next year. And the year after … (196)

The overall and very uplifting message of this novel is one of survival. The orphan girls, largely, survive and adapt. New lives are created, as are children and relationships, and they leave behind snippets of those lives so that, 160 years later, a Memorial Committee in New South Wales and a monumental stonemason from Dublin can try and piece together some kind of a concrete tribute to their survival and adaptability. The metaphor that closes the novel and which Joy Kennedy exploits in her efforts to come to terms with why memorials are necessary at all, relates to the life of birds:

It is their fine art that moves her. They go from where they breed to where they winter. They may travel over the open seas or close to the coasts – even the most private of them become gregarious on these journeys and flock together, often making a comfortable V shape to help them in their travels. They have learned where the sun and the stars are. They move when their pituitary glands feel the darkening evenings. They go to where the food is, a lot like us. Some of them have altruistic tendencies and some don’t – also like us. And there are regional variations in some birdsong. They get their accents and put them in their mouths, so no matter where they are we should know from where they came. (251)

This is a beautifully written novel that gives us a good story complete with empathetic characters. But it is also an intelligent and engaging piece of work that leads us into a face-to-face confrontation with some of the bigger questions concerning memories and journeys.

Rebecca Pelan, University College, Dublin