Not the Same Sky Launch Address, Melbourne, by Mike Richards

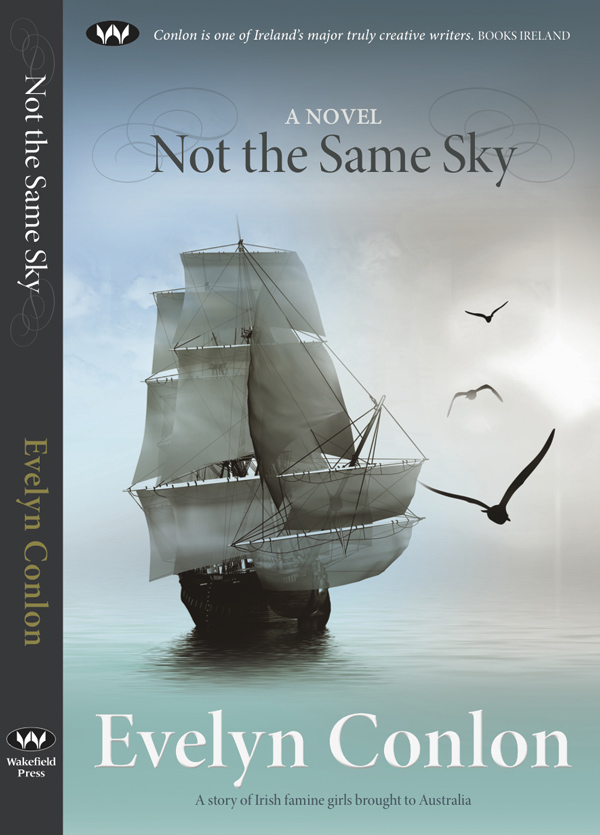

Not the Same Sky – by Evelyn Conlon.

Launch address by Mike Richards at Readings Bookshop, Melbourne, 5 September, 2013.

I’m delighted to be here to launch Evelyn Conlon’s wonderful new novel Not the Same Sky in Melbourne. Her body of literary work is well known and highly regarded in Ireland and her fiction and short stories and essays have brought her much deserved acclaim and national recognition at home; and a growing, devoted following in this country.

I first met Evelyn Conlon more than twenty years ago when she visited Melbourne on one of her many visits after she lived here for several years in the 1970s, and we shared an interest in writing about the atrocity of capital punishment. That shared interest saw Evelyn publish her powerful third novel, focused particularly on death row inmates in the United States, Skin of Dreams, which was shortlisted for Irish Novel of the Year in 2004. It also led to my biography of the last man hanged in Australia, Ronald Ryan, which was published around the same time as Evelyn’s book.

In Skin of Dreams, Evelyn is interested in the imaginative intersection of the past and the present and how the “sometimes cruel mysteries of ancestors play out in our own hopes and dreams”. This is a theme that has animated my own recent book, Wakool Crossing. Following Skin of Dreams, there is something of the same creative impulse in Evelyn in her new work. In Not the Same Sky, she has brought to this novel her distinctive creative sensibility and her great powers of imaginative prose.

Again, across two continents and two cultures, Evelyn’s novel displays through her gift for storytelling her empathetic identification with the disadvantaged and the downtrodden. This deeply researched novel is based on the so-called Irish famine orphans of the mid-19th century. Between 1848 and 1850, in multiple voyages, more than four thousand young women and girls, most in their early 20s but some no more than 14 or 16 years old, sailed to Australia from Ireland via Plymouth. With names like ‘Mary’, ‘Catherine’, ‘Ellen’, ‘Rose’, ‘Jane’ and ‘Sarah’, these young women had been consigned to the workhouses of counties all over Ireland following the famine that had ravaged the country with the failure of successive potato crops; a famine that blighted a generation with poverty, misery, death and disease; a blight that had commonly taken their parents away. They were part of an ill-fated emigration plan devised in London by Colonial Secretary Earl Grey, and they were destined for labour recruitment depots in Sydney, Adelaide and Port Phillip.

While Grey’s scheme might have been animated by liberal motives to spare young women a life of misery in the poor houses, it was ill-considered and short-lived and was scrapped in 1850 after only two years. Evelyn’s book takes us on two journeys of discovery: the first which opens and concludes the novel is the quest of stonemason Joy Kennedy in 2008, who embarks on the long flight to Australia to take up a commission to build a memorial to these Irish orphan girls who made the hazardous journey by sailing ship some 160 years before.

The second journey and its aftermath about which Evelyn writes, forms the centerpiece of the book the three months long voyage of the young women aboard the Thomas Arbuthnot transporting the girls to Australia in 1849. The famine orphan girls were often illiterate, they had little or no domestic training and no hope of better in Ireland when they were wrenched from the workhouses to be shipped to far- off Australia to fill a labour shortage for domestic workers in the growing colonies. (And, as some of you will know, I’m sure, there is a memorial to these young women at Hyde Park barracks in Sydney, the site of their first encounter with the myriad of men who selected them as domestic servants, or in other ways indentured them into their own working and personal lives).

In the novel, we follow the lives of four young girls: Honora Raftery, Julia Cuffe, Bridget Joyce and Anne Sherry as they embark on a journey to a land they have barely heard of, let alone can comprehend in any meaningful way. Importantly, on board they are in the care of Surgeon- superintendent Charles Strutt, who in loco parentis emerges as an entirely benevolent figure. The interactions between Strutt and the girls allow us to feel that their experience as orphans is already somehow being remediated. As Evelyn recounts, the stoicism of the girls and their bravery are extraordinary. These are girls who do not ask much of life but who try to make the most of what they are given. Their uncertainties and fears, their humor in the face of privation and challenge, their resilience to setback, their innocence and naivety these are wonderfully captured by Evelyn in a prose style that is lucid and witty and nuanced and never condescending.

This is storytelling at its best, as these girls’ modest hopes constrained by the harsh realities from which they’ve come are variously realised or dashed in the tentative new beginnings they make upon their arrival in Sydney and beyond. When they travel to their various destinations in colonial Australia, the girls traverse a landscape that is familiar to us, but frequently alien and forbidding to newcomers. Evelyn’s evocation of the girls’ enlivening response to the landscape and its indigenous people, the distinctive flora and fauna of the country, bears the mark of an outsider who is however deeply familiar with its character, its colours and rhythms, and she writes of these things with an artist’s eye.

By the end of Not the Same Sky, we feel like we know these characters; they are just four among 150 abandoned young women plucked from the desolation of poverty, neglect and despair and taken to the other side of the earth to an anxious and uncertain new life. Some of them languish and die prematurely in the harsh new environment, some of them make the best of their meagre opportunities, most of them just muddle through, but none of them ever return to the Ireland of their birth.

While there is a literal quality about the girls discovery on board ship of the different sky in the southern hemisphere perhaps, the harsh quality of the light and the constellation of stars at night, we may take the sky in the title as a metaphor. A metaphor for a raising of the limits of the possibilities in their lives from the workhouses of Ireland to their new lives in Australia. It is not the same sky, nor does their new existence under the Southern Cross carry the same burdens: now there is the relative possibility of choice of safety over peril, of hope over fear, of life over death.

Evelyn’s gift in this beautifully crafted novel is to take us with her in these transformative journeys, and she enables us to better understand the truth of these Irish orphan girls existence, and memorialise their triumph of survival over adversity. Among her many great achievements in this fine book is that she successfully reveals in these girls their simple humanity. It now gives me very great pleasure to declare Evelyn Conlon’s compelling new novel, Not the Same Sky, officially launched.

Mike Richards