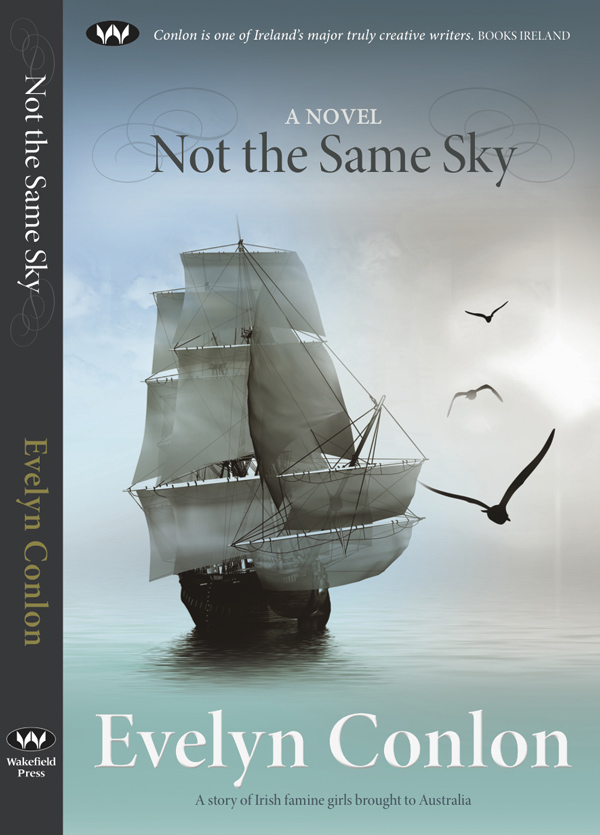

Not the Same Sky Reviewed by Newtown Review of Books

Not the Same Sky by Evelyn Conlon Reviewed by Candida Baker, Newtown Review of Books · 18 September, 2013

Evelyn Conlon sidesteps the traps of historical fiction in this moving story of four young Irishwomen sent to Australia during the Great Famine.

‘Australia without the Irish would be unimaginable. Australia without the Irish would be unthinkable. Australia without the Irish would be unspeakable.’ — Paul Keating, 1992

Irish writer Evelyn Conlon is no stranger to Australia. In the early 1970s she spent six months at Mount Isa, working in a bar, and she’s been a regular visitor since then.

Conlon is an accomplished writer – her last novel Skin of Dreams was shortlisted for the Irish Novel of the Year, and the title story of her wonderful short story collection, Taking Scarlet as a Real Colour, was performed at the Edinburgh Festival.

In this book Conlon takes as her starting point – after a brief, present-time prologue – the tragic aftermath of the potato famine in Ireland that saw more than 4000 Irish girls shipped overseas to Australia. The narrative concerns one group of girls who left England on Sunday, October 28, 1849, on the Thomas Arbuthnot under the able care of Surgeon Superintendent Charles Strutt.

The present-day strand, which bookends the novel, is the story of Joy Kennedy, a sculptor who has been asked to create a memorial to the girls and in the process finds out much, not just about the girls, but about herself as well.

To my mind, historical fiction is a tricky genre. At its worst it can give rise to – and this example is from a book that purports to be about Queen Mary I of England – sentences such as: ‘Somewhere upriver, far from all this kerfuffle, with her newborn son, was the Queen.’ At its best – Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, for instance – it gives flesh and blood to factual stories, and although, of course, we cannot ever truly know those who have died and gone before, we must feel, if the narrative is strong enough, that we do know them, and that yes, this is how they would behave, this is what they would do under these circumstances.

Conlon achieves this difficult task admirably. By concentrating on four of the girls – Honora, Julia, Bridget and Anne – and on the upright and commendable figure of Strutt, she gives us the chance to emotionally engage with each character as they traverse the unknown landscape of loss of family and friends, the massive journey by sea, the brutal relocation to wherever is determined by the authorities, and their individual abilities (or lack of them) to cope with this tragic severing and what would certainly be described now as post-traumatic stress disorder.

But this is not a tragic book. In the same way that the girls, and Strutt himself, prove resilient, Conlon’s prose is by turn poetic, acerbic, spare and beautifully descriptive. She wears her attention to detail and research as the lightest of cloaks, bringing to life the daily routine on board ship with moments of poignancy and humour.

They pass the halfway mark of their journey when the northern sky is replaced by southern stars and their first Christmas away from their families comes upon them. It is all too much, and to Strutt’s distress, they begin a lament – a caoineadh – for all they’ve lost. Strutt cannot bear the mournful sound and is mystified when suddenly the mood changes and the girls break into laughter. In that moment he suddenly understands the difference between an English and Irish sensibility.

The girls are survivors – mostly. They adjust to this strange new landscape, many of them sent from Sydney deep into the country with its dusty palette of colours, strange animals and colourful birds. They make lives, work, get married, have children – they write diaries and collect mementoes, and centuries later these are part of the information given to Joy Kennedy while she tries to grapple with what a memorial is, and why it is worth creating one at all, when of course what she is coming to terms with is mortality, her own and other people’s.

This book is fundamentally about journeys – both external and internal. How is it, Conlon asks, that the same circumstances can befall a group of people and yet their reactions, and the consequences of those reactions, can be quite different for each individual?

One of the girls asks, after an ‘incident’ on the ship:

‘What does a voyage mean?’

‘It’s a journey.’

‘Ah.’

‘What happened?’

‘Nothing. It’s the same as a journey?’

‘Yes’

‘Do you come back from it?’

‘I don’t know.’

And therein lies the rub – we don’t know. We undertake our quests and voyages because we must, and all of them lead to the ultimate, unknowable journey. Conlon brings all this to bear and more in this beautifully formed novel.

The book was launched in Sydney in August by Dr Jeff Kildea – an historian and Adjunct Senior Lecturer at the Global Irish Studies Centre at the University of New South Wales. Kildea has written extensively on Irish Australia, and for those who are interested, his speech can be found here.