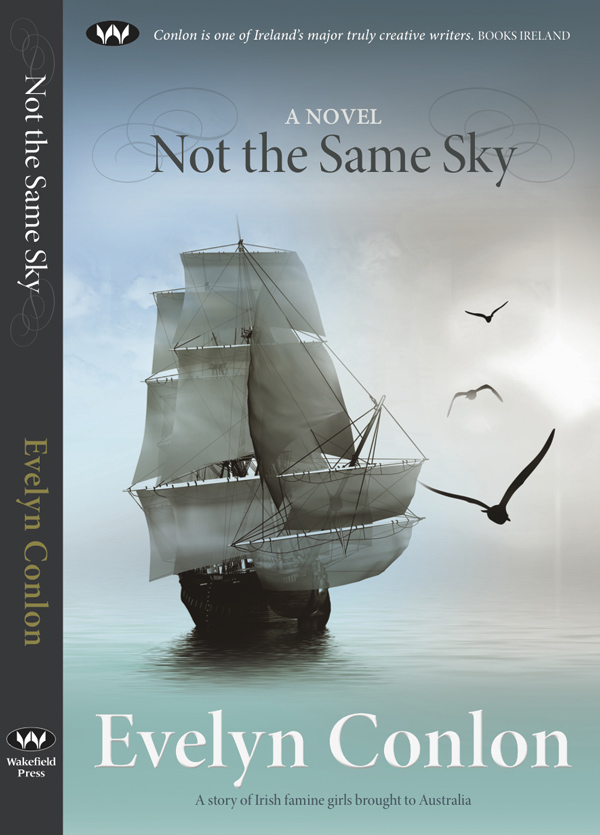

Not the Same Sky Reviewed in MC Reviews

Not the Same Sky Reviewed by Julie Kearney in MC Reviews, Brisbane, 6 February, 2015

Not the Same Sky, the latest novel of Irish writer, Evelyn Conlon, was at first too cool for me, too much like a sociological case study. I did not warm to the largely second-hand reporting of the lives of some of the 4414 real-life Irish girls aged between fourteen and twenty years who were shipped off during the Irish Famine to the Australian colonies by the British Government as a source of cheap domestic labour. The fictionalised girls Conlon singles out ‒ Honora, Bridget, Anne and Julia ‒ never take on a full-blooded life of their own. Gradually, however, I came to realise that there was ‘method in the author’s madness’. The emotional worlds of the bewildered adolescents are only hinted at and it is by the creating of these gaps in their lives that Conlon is able to suggest the intensity of their different experiences as they drop without trace into a new and harsh world.

Reading Not the Same Sky, I was reminded of another book by Australian historian, Lucy Frost, titled Abandoned Women. A documented rather than fictional account, it deals with the fates of destitute Scottish women convicted of petty thefts and transported to Van Diemen’s Land. Frost’s research into the background of their lives is one of the most intriguing aspects of her book. Though she admits she was frequently frustrated by the gaps and omissions in official records, she nevertheless manages to re-create in sparing but moving prose, a vivid picture of what life must have been like for women so abandoned in their morals as to be cast out of society, or alternatively, women abandoned by their husbands and thus by society.

Conlon’s medium is fictionalised history so she was not limited in the same way as Frost. Nevertheless she elected to portray her subjects similarly, in her case through the kindly eyes of a witness, a young man called Charles Strutt who was Surgeon-superintendent on board the Thomas Arburthnot when it sailed from Ireland with its cargo of famine victims. She did not choose to seize the opportunities offered by fiction to follow the girls in any depth into their new lives and what she achieves as a result is analogous to Frost’s work: a narrative made more powerful by its ellipses, by its understatement of the harsh experiences endured by adolescent girls forced to emigrate to the far ends of the earth.

Thus it is Charles Strutt rather than his charges who unwittingly becomes the hero of Conlon’s tale. Given their traumatised backgrounds and the further trauma they are undergoing, the girls are fortunate to have Charles for their protector. It would be interesting to know what the author found in the real-life Charles Strutt’s diaries to base his character on, because I found his punctilious, motherly fussing over the girls somewhat unbelievable. But then, as they say, truth is often stranger than fiction.

Strutt’s character is fleshed out in detail whereas the characters and lives of his charges are restricted to vignettes, and initially, as I said, I found this frustrating. They are after all the subjects of the novel and I wanted to know more about them, not about their male guardian. But as the story progressed I finally got it. There is a poignant irony in the parsimonious detail given. These young girls who had no control over their lives were sent as servants to the colonies, there to disappear like stones thrown into a pond, and in a way it is fitting that their fate is evoked in the way Conlon has chosen. To do otherwise would be to falsify their stories which to this day remain largely unknown. Instead, through isolated images, fragments of diaries and slipped remarks, Conlon manages to convey something of the truth of the inhuman experiment conducted upon them as well as providing a moving account of the dislocation and loneliness they endured.

If anything, I found the account of the fortunes of these child-women once they arrived in Australia a trifle benign. When you consider the culture of sexual abuse and paedophilia that they faced in a population dominated by sex-starved men (so ably researched and documented by Lucy Frost in her study of the Scottish women) there must have been some real horror stories to tell. Perhaps Conlon’s fictional girls were among the lucky ones who escaped the unpleasant fates so often met with by isolated girls in nineteenth century Australia, or perhaps she just didn’t do enough research.

‘A lot of hitting went on,’ reflects one of the girls in the country town to which she has been sent, but otherwise we hear no more of the notoriously violent side of the society the Irish girls were entering.

That said, what impressed me in Not the Same Sky was Conlon’s use of understatement in the brief sketches she gives of the emigrant girls, particularly Honora who is the main character:

‘Honora looked at the crowd of girls on the quay. She knew there was a house and a mother and a father and maybe sisters and brothers behind all of them. But in the past only. Standing here, everything was past. That meant it was gone.’ (35)

On board ship she looks at the sky:

‘She wanted to believe this was the same sky that was over the home she had just glimpsed on the map, the one she had been taken from and would never see again….Who could ever come back from so far? If she could believe it was the same sky surely that would help.’ (58)

And more tellingly, when Charles, having married and settled in Australia, meets up with one of his former charges, Anne Sherry, she tells him she now has several children from two marriages. She notices his dubious expression:

‘I don’t say how many from each. They are children. People should mind children,’ she said. Charles felt uncomfortable.

‘Oh no, it was too late for us,’ Anne said, reading his mind. ‘You did your best to get us here.’ (187)

A motif of birds weaves through the narrative, beginning with Bridget’s interest in the feathered attendants of her voyage. A gentle girl, she recognizes one bird as accompanying the ship, insisting in the face of scepticism that it is the same bird. The allegorical meaning of birds is made clear in the framing story of the novel. In the twentieth century an Irish sculptor, Joy Kennedy, travels to Australia in response to a request to erect a memorial to the forgotten girls. Having traced the journeys of the girls and seen the places where they lived when they arrived in Australia she muses about migratory birds:

‘But it is the flight of birds that interests her most. . .They go from where they breed to where they winter. They may travel over the open seas or close to the coasts . . .they get their accents and put them in their mouths, so no matter where they are we should know from where they came.’ (251)